Joyce Crenshaw Henderson pushed a stroller along the smooth brick walkway, its sunshade pulled down to shield her 3-month-old grandson from the intensifying sun rising in a cloud-dappled blue sky.

Her path was clear past the newly dedicated Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia to her left and, to her right, roomy rows of white plastic chairs directed toward a lectern. She was en route to meet a group of fellow descendants of those enslaved laborers sitting at a picnic table in the shade.

“Are you double vaxxed?” the women asked before hugging one another for the first time in many months. They gathered around the stroller and through their masks cooed over the sleeping baby — his cheeks, his tiny red Nike socks (which would soon come off and prompt even more cooing over his tiny toes).

“The next generation,” Henderson said proudly. The name of her own great-great grandfather, James (Jim) Henderson, is etched on the wall of the nearby memorial.

The baby’s presence was a suitable reminder of why Henderson and other descendants were gathered Wednesday morning: Gov. Ralph Northam ceremonially signed HB1980, which establishes the Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Program, into law.

Del. David Reid (D-Loudoun) introduced the bill in January’s legislative session. The General Assembly passed it in February, and Gov. Northam officially signed it into law in March.

“The Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Program is established for the purpose of reckoning with the history of the Commonwealth, addressing the long legacy of slavery in the Commonwealth, and acknowledging that the foundational success of several public institutions of higher education was based on the labor of enslaved individuals,” reads the first section of the law.

UVA President Jim Ryan spoke first, acknowledging the Monacan Indian Nation, the traditional custodians of the land upon which he and the other attendees stood, saying that it’s important to look to the past to build a better future. He also pointed out the symbolism of holding the ceremonious singing of a bill designed to break cycles of racism and poverty that have been foisted in many forms upon generations of Black Americans, in front of a memorial designed to invoke a broken shackle.

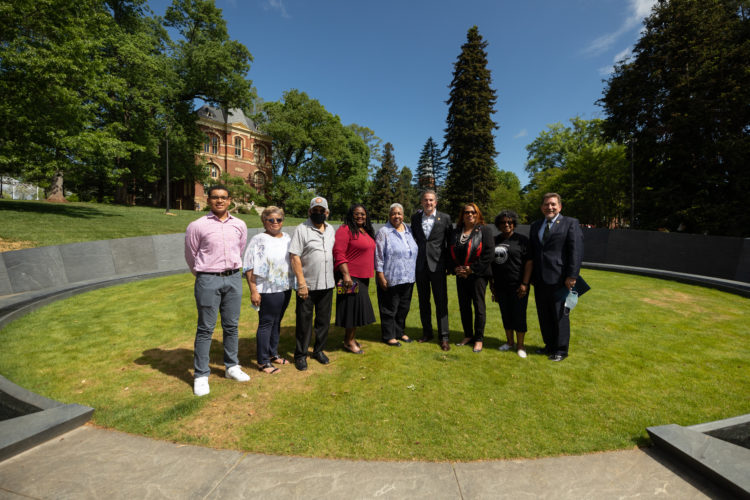

On Wednesday, May 5, Governor Ralph Northam ceremoniously signed HB 1980 into law while the Rev. Carolyn Dillard, Robin Reaves Burke, Del. David Reid, Del. Sally Hudson, and UVA President Jim Ryan looked on. Mike Kropf/Charlottesville Tomorrow

The law outlines that five public institutions of higher education in the state — UVA, Longwood University, Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia Military Institute and the College of William & Mary — are to establish and implement a “tangible benefit such as a college scholarship or community-based economic development program for individuals or specific communities with a demonstrated historic connection to slavery that will empower families to be lifted out of the cycle of poverty.”

These five schools were established before the abolition of slavery in 1865 and built and maintained by enslaved laborers. One line in the law states that other private schools throughout the commonwealth with a similar history are “strongly encouraged to participate in the Program on a voluntary basis,” and Reid hopes they will.

Other schools around the country are working on school- and community-based acknowledgement and reparations programs, too, perhaps most notably Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., which announced its efforts in October 2019.

These schools cannot use state funds for these programs, nor can they increase tuition and fees to cover the costs, and they must collaborate with the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) to establish program guidelines no later than July 1, 2022.

Additionally, HB1980 mandates that schools must establish “guidelines for the identification of enslaved individuals who labored on former and current institutionally controlled grounds and property, the development of appropriate means to memorialize these individuals, the development of programs for individuals and communities still experiencing the legacy of slavery to empower them to break the cycle of poverty, eligibility criteria for participation in such programs, and the duration of such programs.”

Though the law outlines potential for these schools to enact real, equitable change within those communities of descendants, whether that actually happens depends on the yet-to-be-established guidelines and how SCHEV and the individual schools choose to fill out some of the bill’s more general language and provisions.

With the construction and recent dedication of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers as well as the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University (convened in 2013 by then-president Teresa A. Sullivan), among other initiatives, UVA has already taken steps toward some of the law’s requirements. Even before Reid brought HB1980 to the General Assembly, members of the university’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers Community Engagement Committee were talking about some sort of scholarship program for descendants.

But in order for the descendants of enslaved laborers to participate in and benefit from any such program outlined by the new law, they must first be identified.

During the pre-signing remarks, Robin Reaves Burke, one of Reid’s constituents who is also a descendant of Mary Hemings, Sally Hemings’ older sister, pointed out that Thomas Jefferson was “a meticulous record keeper,” especially in regards to his property, which included people, both at Monticello and the university. Those records have allowed her family to confirm its oral history.

Similarly, some people in the Charlottesville area, like Henderson (who herself worked for UVA Health for more than 40 years before retiring in February), know their lineage through both stories and records. Others do not.

Through the university’s Descendant Project, genealogist Shelley Murphy has been working for a few years to determine the names and identities of the enslaved laborers who helped build UVA and connect them to their descendants, many of whom have worked and currently work at the university. She works with university organizations as well as a local independent nonprofit, Descendants of Enslaved Communities at the University of Virginia, as well as individual people and families, on that mission.

DeTeasa Brown Gathers, a lifelong Charlottesville resident, longtime UVA employee and mother to a UVA alumnus, co-chairs the engagement committee and serves on the board of the Descendants of Enslaved Communities group. She has deep ancestral roots in the area and pointed out after the ceremony that so far, Murphy and others have been able to add the names (and in some cases, occupations) of about 500 enslaved laborers to the wall, a huge accomplishment. But there are more than 4,000 spots total, and there’s much work to be done.

“Even though there was so-called ‘excellent record-keeping,’ some people were left out,” Gathers said, and their descendants deserve to be eligible for these programs, too. “Those are definitely the pieces that we need to be pushing on and trying to figure out,” she said. “We have a lot of first names [with] no last names.”

Still, Gathers is excited about the bill and what it could mean for individuals, for families. “This really is a way of dismantling systemic racism, and just the start of it,” she said.

What’s more, while the bill outlines that each institution must work with SCHEV, it does not specify that descendants groups should be part of the decision-making process, though if righting past wrongs and ensuring a more equitable future programs is what the law and the schools seek — as Reid, Northam, and Ryan all claimed in their remarks Wednesday morning — it would certainly behoove the schools to do so.

Each school’s program will be slightly different, said Reid, reflecting each institution’s specific relationship to slavery and the people whose labor it exploited. For instance, Longwood University, originally founded as a women’s seminary in 1839, does not have the same volume of records, or records as detailed as those kept by UVA and Jefferson, said Reid. Thus, Longwood’s program might end up being focused more on community programs than individual scholarships, Reid speculated in an interview after Wednesday’s ceremony.

The Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Programs are to remain in place, says the law, “for a period equal in length to the period during which the institution used enslaved individuals to support the institution or until scholarships have been awarded to a number of recipients equal to 100 percent of the population of enslaved individuals identified […] who labored on former and current institutionally controlled grounds and property, whichever occurs first.”

This is another spot where the number of scholarships or the reach of community programs could vastly differ based on the guidelines UVA and SCHEV choose to adopt.

Though UVA was officially established in 1819, it began using slave labor two years before, when Thomas Jefferson directed 10 enslaved people to clear cornfields to make way for the Academical Village. Enslaved laborers rented by the university from local white landowners worked alongside free Blacks and poor whites to build the physical university, and to keep it running — cleaning classrooms and the library, cooking, ringing the bells, keeping the grounds, and much more — once the school began enrolling sudents. Students were not allowed to bring their own enslaved people to Grounds, but faculty could and did. There are many accounts of students and faculty mistreating and abusing these people. And, when slavery was abolished in 1865 and many of the previously enslaved folks were free, the university hired them back to work their previous jobs without acknowledging their freedom.

For UVA, that’s 48 years of enslaved labor, from thousands of people.

The Rev. Carolyn Dillard, the University-Community Liaison in the Division for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion at UVA and a member of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers Engagement Committee, delivered remarks that highlighted how she is always honored to stand on “this hallowed ground,” a UNESCO World Heritage Site that enslaved laborers helped to build and restore. Mike Kropf/Charlottesville Tomorrow

Peter Blake, director of SCHEV, says that the organization has had some internal meetings to determine which staff will be involved in the decision-making process with the schools, but that’s about as far as they’ve gotten. SCHEV is also waiting to hear who they’ll be working with from each school.

Therefore, discussions have not yet happened regarding any monetary amounts or where that money will come from, what the community programs might be, how many scholarships will be given out annually, or whether a descendant will have to gain admission to a school in order to be eligible for a scholarship program without some sort of ongoing academic assistance if necessary. As for the general nature of some of the bill’s language, he says that the potential it gives schools to establish scholarships and/or community development programs that “could turn into something very robust, and also very locally-determined and mission-specific.”

The Rev. Carolyn Dillard, a direct descendant of Ann and Jefferson Cross, who were enslaved and raised their family at Castle Hill in Keswick, sees the Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Program as “an opportunity to be heard,” and for her ancestors, for others’ ancestors, to be “seen and be recognized as builders, as creators, as inventors, and to be acknowledged.”

“It is our hope to reunite” descendants with the names, occupations, and work of their ancestors, and to bring together individuals and families with similar lineages “for the repair and healing, to provide a trauma-informed care opportunity for them to express themselves and begin the healing process,” added Dillard, who also is UVA’s University-Community Liaison in the Division for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion.

Dillard, Gathers, Henderson, and others hope that this is just the start of a process that could (and should) continue for generations, and it’s up to the schools and SCHEV to ensure that happens.

It could be the start of intentionally creating more opportunities for those descendants who are right now wearing tiny red Nike socks and sleeping through ceremonies and coos in the shade of a tree on the grounds of a school their ancestors created years ago, in the hands of a community their elders maintain to this day.

Community members and descendants of enslaved laborers from around the state stand with Gov. Ralph Northam and Del. David Reid, who introduced the bill to the General Assembly in January, in the center of UVA's recently dedicated Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. Mike Kropf/Charlottesville Tomorrow