Determined

This series uses the Social Determinants of Health as a foundational framework and guideposts to bring you stories of how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted some of our African American communities.Stacey Washington feels blessed these days. She’s 41 years old, has six healthy children — five adults and an 11-year old — and three grandkids. She works for the city of Charlottesville’s Office of Economic Development and makes a decent amount of money. She’s got some savings and a place to live.

“Don’t get me wrong, I won’t complain because I have a place to live, but I would like a nicer place,” said Washington. “I feel I deserve it, and I can afford it.”

But it’s not that simple. Townhouses, apartment complexes, private landlords — each time, she pays a fee, submits a rental application and they tell her it looks good.

“But as soon as they run my criminal background they say no” she said.

Washington has several past larceny convictions. So she explains this to prospective landlords. “They say, ‘Well, OK, we’ll see what we can do,’” she said. Then, she gets an impersonal email from them saying her application was denied.

What’s worse is that now she makes too much to qualify for low-income subsidized housing, and if Washington’s current landlord decided to sell her place, which she could do at any time, she’d be homeless. “With all of my money, with my good job and everything, I’d be homeless, because I don’t have the option to just go and rent a place,” said Washington.

Home to Hope Peer Navigator Stacey Washington

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

Washington is a peer-navigator for the city’s recently created Home to Hope, a resource program for people returning home from jail or prison. She sees these barriers at almost every juncture — housing, jobs, access to healthy food. It’s part of why Home to Hope exists — to give a fighting chance to people whose pasts are constantly held over and against them, said Washington.

“I’m very intelligent, I’m articulate, I just come with a little bit of baggage,” she said. “I can put that baggage down if you allow me. But you’re the one that keeps making me pick it up every time you ask me these questions.”

Washington also knows that if she, with all her success, still faces these barriers, that it’s much harder for program participants who haven’t made it this far yet.

“I know what my participants go through, because I’m going through it myself right now,” she said.

Growing up in Charlottesville, the only resources people told her about were the Department of Social Services and the Women, Infants and Children program. Washington said she’s been incarcerated in every women’s prison in the state, and none of them offered her resources.

“They don’t tell you about them,” she said. “They keep them hidden and they give people preferential treatment. A lot of resources are through nonprofit organizations, but if it’s not-for-profit, why do I have to be so privileged to know about the resources? Why are agencies not telling me?”

While Washington was incarcerated, her daughter connected with Ridge Schuyler, the dean of Piedmont Virginia Community College’s community self-sufficiency program, who also helped found the Network to Work job skill training and placement program. There, her daughter trained to become a certified nursing assistant. The program is amazing, she told her mother.

When Washington was released, her daughter introduced her to Schuyler and Frank Squillace, the director of Network to Work. She was interested in the weekslong program but needed a job immediately. Nobody would hire her, though, because of her criminal record. But she knew the manager at Panera Bread, and got a job. There, Schuyler would come in for lunch, ordering the strawberry poppyseed salad every time. “From that day forward we built a relationship,” she said.

Now, Home to Hope has a seamless partnership with Network to Work, as they work with some of the 90 program participants to lay out their path forward. Life is like driving a car, Washington said. It’s important to check the mirrors to make sure the past doesn’t creep up from behind. “But if you drive your car looking through your mirrors, you’re going to crash,” she said.

“You could not bring him back with you”

As a child, Mayor Nikuyah Walker went with her great-grandmother to state prison to visit her youngest son, Walker’s grandfather. Back then, they were allowed to bring picnic baskets of food.

“I remember her heart breaking each time she was preparing the food, and when she had to leave him there, because while you could take him all of his favorite foods, you could not bring him back with you,” said Walker. “And I remember just that quiet, intense sorrow.”

As a teenager, Walker watched cousins, her same age, get incarcerated, spending more than a decade in prison. She remembers sitting in a Charlottesville courtroom and seeing the judge call her cousin “garbage.”

“From the bench, this white judge said, ‘You’re garbage’ and no one did anything,” said Walker.

Walker has been the main driving force behind launching Home to Hope, drawing inspiration from these memories, though the program’s real genesis, she said, is owed to former City Councilor Holly Edwards, who died in 2017 but first saw the need and envisioned it.

Mayor Nikuyah Walker

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

Walker wanted the program to do two things. She wanted the peer navigators, who themselves have been locked up, to be the first people participants see when they’re released — to build relationships and trust and advocate for them. There are other re-entry programs in the Charlottesville area — Healthy Transitions, the Offender Aid and Restoration program — but Home to Hope is the only one whose entire staff has experienced incarceration.

Walker also wanted the program to allow navigators and participants to learn that, on their own journey of healing from deep levels of trauma, they could help others heal as well, while also earning close to a living wage with a starting hourly salary of $18 an hour, she said.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, at least twice a week Home to Hope staff went to the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail (ACRJ) to talk with inmates about their upcoming release — to develop short and long term goals, and discuss what’s called a Wellness Recovery Access Plan (WRAP).

“We are not only asking people with Home to Hope about jobs, but we are asking them about careers and those dreams they have probably given up a long time ago,” said Walker. “It’s been something that I have hoped for a long time someone would fix.”

“It feels very deflating”

Whitmore Merrick, a Home to Hope peer navigator, said much of Home to Hope’s efficacy lies in its ability to connect one-on-one, and in-person, with participants. But since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ACRJ, to prevent an outbreak, has not let outside visitors other than attorneys in, making it more difficult to connect with people in jail, he said.

Merrick would also normally have spent the last two months introducing participants to outside partners, helping them build their own networks. Peer navigators had planned to host a giant in-person event called “Hope Starts Here” to do exactly that, but with the pandemic, they switched to a virtual Zoom version.

Several dozen people showed up, including area housing and resource providers. Washington relayed some of her life experiences, explaining how rules and regulations have prevented her from moving forward. Merrick agreed, saying there needs to be more ways to hold boarding house landlords accountable. The units are old and neglected, having not been renovated in decades, but because housing is scarce, they get away with it.

“We’re dealing with slumlords, to be quite honest,” said Merrick.

Peer navigator Ramanda Jackson raised another key issue. When people return from jail or prison, they often go back to whatever support structures they have — family, close friends — especially to find a place to live. But, she said, it’s almost impossible to get a person with a criminal record added to a lease.

(From left to right) Home to Hope Peer Navigators Whitmore Merrick, Stacey Washington, Ramanda Jackson and Shadeé Gilliam.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

One participant in the program currently lives at the Salvation Army, she said. He’s working and has a housing voucher.

“He went to all these different landlords, and even though he had the money to move in, and the voucher to back him, because he also had a record, they denied him,” said Jackson. “I don’t care what kind of money or voucher you have; you cannot live in this neighborhood in Charlottesville.”

Jackson told him to keep trying, that all he needs is one person to say, “yes,” but it’s hard, she said. “It feels very deflating,” said Jackson, who has a felony conviction from 26 years ago. “I paid my debt to society, and now you’re telling me that I still have to fight this just to have somewhere to go?”

Shadeé Gilliam, also a peer navigator with the program, said he’s talked with some landlords who have had outrageous requirements for prospective tenants, imposing rules on when and how often they can have guests or the hours they have to keep.

“It made me question whether the landlord even saw the participant as a human being,” said Gilliam. “You’re not outright telling me no, but you’re putting me in a position where I definitely don’t want to be here.”

All navigators agreed that housing, especially for those with criminal records, who also don’t have savings or living-wage jobs, is nearly non-existent in Charlottesville, especially with the pandemic cutting down on the number of people moving.

Washington said that despite these obstacles, she sees participants’ determination. She’s been working with a woman she was incarcerated with. She was released from jail into Region Ten’s Women’s Center at Moore Creek, a residential substance treatment facility, where she stayed until her insurance ran out. She had nowhere to go, though, so Washington and the Home to Hope team got her a hotel room until she was able to move into one of the homes maintained by Oxford Houses, another recovery program.

Now, she’s in drug court and passing the drug screens, she has a job and is doing well, said Washington. “She could have gotten high and given up after the Women’s Center, but she didn’t, she contacted me,” she said. “She didn’t have to go to the Oxford House, but she did. That’s a success.”

Eddie Harris, the head of Ready Kids’ Real Dads program, has worked with incarcerated fathers for years, and serves as a mentor for many Home to Hope participants and peer navigators. As good as these outcomes are, Harris said, the work isn’t done until the system is changed.

“Until there are opportunities for everyone, I think it’s really hard to point success out,” said Harris.

“That’s the problem”

Legal Aid Justice Center community organizer Harold Folley

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

Years ago, Harold Folley applied for a job at the University of Virginia Medical Center to clean rooms at the hospital. He was acing the in-person interview, but the interviewer’s body language shifted when he saw Folley had checked the box asking if he’d been convicted of a felony. His interviewer paused, and told Folley, “I don’t think we’re going to hire you, because the nurses will probably think you’ll steal some drugs off their carts,” recalled Folley.

For the last two years Folley has worked as a community organizer with the Legal Aid Justice Center’s Civil Rights & Racial Justice program. For the last three years, he’s worked as a facilitator with the People’s Coalition, a grassroots organizing group that pushes for transparency and accountability in the criminal justice system.

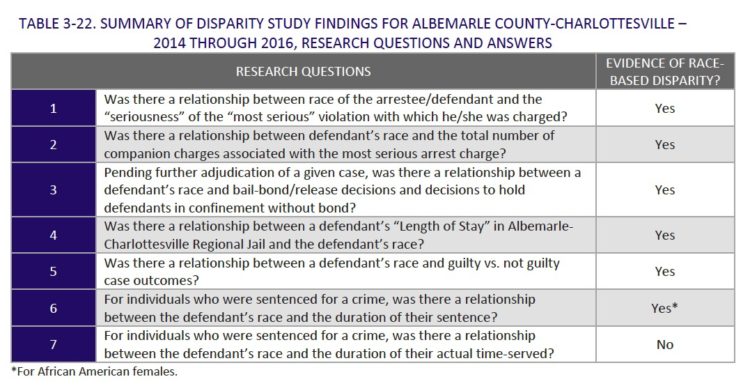

Since the pandemic, Folley’s been crafting a series of recommendations to the City Council in response to a 135-page study released earlier this year by the MGT Consulting Group that looked for racial disparity in a 2014-2016 chunk of data from the ACRJ. At almost every juncture, the study found disparity with how Black inmates were treated as compared to white inmates — they serve twice as many days in jail when convicted for comparable crimes with similar criminal histories and similar accompanying charges; they are 31% more likely to be found guilty for the same charge; they are more likely to be charged with accompanying crimes; they are more likely to be denied a bonded release.

Credit: MGT Consulting Group

The study showed what happens to people after they are charged, convicted and incarcerated, but Folley wants to know about the front-end — what about the American legacy of policing, and criminalizing race and economics?

There are multiple points along the criminal justice system where the discretion of law enforcement officials is key — police, magistrates, commonwealth attorneys, judges, probation officers — they all have leeway to make a range of decisions, inevitably informed by their worldview. But officials who oversee many of these critical junction points did not provide the research team with data.

“That’s the problem, the first contact in the criminal justice system is the police department,” said Folley.

In 2016, however, a city-funded study of the juvenile criminal justice system revealed significant levels of racial disproportionality. Black children were reported, arrested, placed on probation, sent to court,and stopped and frisked more often than white kids.

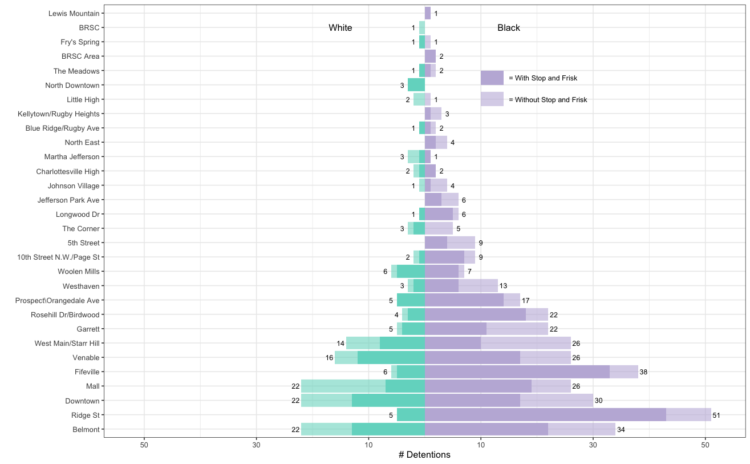

To shed more light on how police-level interactions contribute to the racial disparity and disproportionality in the criminal justice system, the University of Virginia Equity Center’s Michele Claibourn and Sam Powers created a new website and map for the “Determined” series. With Charlottesville Police Department data from 2012-2014 and 2016-2017 gathered through Freedom of Information Act requests over the years from attorney Jeff Fogel, the site details the racial disproportionality that exists when police stop residents on the street.

The Equity Center analysis found that police conduct an average of 11.9 stops per month, and that 65% of these stops result in a search or frisk. Racially, it found that for every two white residents police stopped, they stopped five Black residents.

Credit: UVA's Equity Center

The data are reliably broken down between only Black and white residents — no other races or ethnicities. When Charlottesville’s total population is similarly broken down, removing all others, Black residents make up 21.2% and white residents 78.8%, according to the U.S. Census. But, according to the Equity Center analysis, Black people made up 68.3% of the people police stopped without frisking or searching them, and 72.4% of those they stopped and frisked — nearly four times what is racially proportionate. The site details the reasons that police cited for the stops as well, careful to stipulate that the nature of a stop does not mean a crime has been committed, nor an arrest made.

The data speak to a reality Black residents have long relayed, that their communities are over-policed. In the Orangedale and Prospect neighborhood, where 57% of the population is Black and life expectancy is 6.2 years less that of white residents a mile away — Black residents make up 77.2% of the people police stopped.

Credit: UVA's Equity Center

In the Ridge Street area, which includes the Sixth Street and South First Street public housing neighborhoods along with Friendship Court, 40% of the population is Black and life expectancy 8.9 years less than nearby white neighborhoods. There, Black people made up 91% of the people police stopped — 51 of the 56 stops. In the Locust Grove and Martha Jefferson neighborhoods, where 90% of the current population is white, police stopped people just three times over the same time period: two white, one Black. This means that police stopped people in these white neighborhoods, which historically contained racist covenants preventing Black people from living there, more than 19 times less than in the Ridge Street neighborhood a half-mile away. This pattern holds true for other historically racially restricted neighborhoods as well: Fry’s Spring, North Downtown, Little High, Rugby, Jefferson Park Avenue, and more.

Credit: UVA's Equity Center

The MGT Consulting Group study strongly recommended the formation of a “fully functioning, independent” Civilian Review Board (CRB). Earlier this year, City Council approved an initial CRB, which has gone through many trials to get this far but stopped short of granting it investigative reach or the disciplinary power advocates wanted. Folley said he’s holding out hope because the council funded it with $150,000 in the recently passed fiscal year 2021 budget, and incoming CRB members can redraft the groups bylaws, potentially opening the door for more authority later this year.

But beyond a CRB, the racial disparity report’s first recommendation was to fund re-entry programs, like Home to Hope, to assist people coming home “with housing, education and job training so those labeled as ‘criminals’ can realistically obtain higher-paying jobs and viable, rewarding career paths.”

And while any future data from the police department, magistrates and courts will surely be the ultimate lens of how personal racial bias exists in each areas, the report highlights what sociologist Joe Feagin called, “indirect institutional discrimination” — the laws, public policies and procedures enforced by law enforcement that appear to be race-neutral in their language, but which are racist in practice.

“I just hope we can make more change”

As uprisings, marches and protests have erupted through the country in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, Whitmore Merrick has watched closely, looking for ways that greater systemic shifts might occur. “I feel there’s so much overwhelming pain,” he said. “I just hope we can make more change.”

As someone with a felony conviction, Merrick said he’s felt disregarded by many decision-makers over the years. So he finds hope when, like earlier this week, he gets to talk with someone like Democratic Del. Sally Hudson. He told her he’d like to see three significant changes from the state.

Merrick wants an easy way for people who have served their sentenced time to have the chance to expunge their records. He also wants a way to ensure that drug-related convictions don’t prevent people from accessing government funded benefits, such as housing or financial aid for school. And his last big push is to ease child support requirements for fathers while they’re incarcerated. All three of these have a bevy of ripple effects, he said, that cost the greater society, all in an attempt to continue punishing individuals already being punished.

Hudson too relishes opportunities like these to talk to people like Merrick who are on the ground doing the hard work. “You don’t have the governor’s staff in your cell phone, but I do,” said Hudson. “My job is to be a funnel for those voices in the community.”

Merrick’s also had positive conversations with the city and county commonwealth’s attorneys and the local sheriff’s offices about making significant changes and incorporating Home to Hope into their network of solutions for those facing charges.

“I speak to the people,” said Merrick. “So to be able to pass that on and to have those conversations with the people able to make change, that gives me hope.”

In early April, Hudson and 16 other delegates penned a four-page letter to Gov. Ralph Northam, calling his attention to the more than 57,000 incarcerated Virginians — 58% of whom are Black. The lawmakers asked Northam to release children held by the Department of Juvenile Justice, as well as adult prisoners through geriatric parole, clemency and the power of the pulpit. He should call on commonwealth’s attorneys to reconsider bond and release all eligible pre-trial prisoners, nearly half of the state’s jail population. To date, the state has released only about 200 people in response to the pandemic.

Instead, prisoner release has fallen to local leaders. Since March 17, Folley and a team of activists and local law enforcement officials have worked to figure out how to reduce the number of people police arrest and the number of people being evicted from housing while increasing the number of people being released from jail.

“It’s a deathtrap for people who are incarcerated,” said Folley. “Folks in jail don’t come out and get COVID, people who work in jail bring it in with them.”

He’s still working to get the last eligible people, about a dozen inmates, out of the ACRJ, he said. He asked UVA to temporarily house them in some of its empty dormitories, but they said no, adding that they needed to be renovated instead, he said.

“Voters get lost in the crossfire”

At the core of much of the structural and systemic racism occurring throughout the state, said Hudson, is a very strong governance tension between where the state should step in — by setting the tone or providing resources or guidance — and where it should step back and grant more authority to local governments.

Localities like Charlottesville are clamoring for change — whether it’s taking down Jim Crow-era statues, or tasking a CRB with subpoena power, or revamping its affordable housing strategy — but the Dillon Rule says localities can only do what the state expressly says it can. Hudson said this is “maddening” for those who want things to change. “But people who want to preserve the status quo love those binds because it lets them off the hook,” she said. “They say, ‘I would if I could, but I can’t, so I won’t.’”

For instance, localities want law enforcement to stop criminalizing poverty and over-policing Black people, but a significant part of over-policing, and the resulting racial disparity, stems from counties and cities raising money through the fines and fees that result from those policies, said Hudson, adding that this comes, in-part, from a lack of state incentives and funding.

Or, take sheriffs and commonwealth’s attorneys — two of the major decision-points within the criminal justice system. Both positions are required, under the state constitution, to be elected to office. This strongly encourages these officials to act as extensions of the political parties, said Hudson. “It concedes from the outset that justice is a political tool,” she said.

This structure finds its roots in the 1902 constitution. The same constitution, written by white men, which codified a poll tax to vote, and implemented literacy and property requirements, reducing the more than 146,000 eligible Black voters to less than 15,000 the next year.

In 1971, the state constitution was rewritten and re-ratified, supposing to be the first colorblind constitution. But in it, these locally elected law enforcement positions were more firmly cemented as, again, local governments depended on them for revenue to operate. “We really do have justice by geography, and it all sits in the hands of a handful of local elected officials who have enormous discretion to do what they want,” said Hudson.

Because the General Assembly is normally only in session for two months each year, it makes it difficult to keep pace with the amount of authority and discretion localities are increasingly wanting, though they make efforts. Earlier this year, Northam signed a bill that Hudson supported. It gives school principals the discretion to not report students for misdemeanor offenses.

“Everybody else in the justice system has discretion, teachers are just asking for the discretion to decide what’s best based on what they’ve seen,” said Hudson.

Many Republicans opposed the measure, saying that some forms of sexual violence against girls could be considered misdemeanors and should be required to be reported. Hudson pushed back, saying this was weaponizing people’s biased fear. She pointed to the thousands of times white people have attempted to justify lynching Black men by citing unproven, and often false, accusations of sexual assault. With this new discretion, she said, there are more opportunities to intervene at a local school level, to avoid letting people’s racism and bias determine Black children’s outcomes, sending them into the criminal justice system.

All of this back and forth over who exactly has the authority and power to change these hidden and seemingly small, but practically huge, decision points, can be confusing, Hudson said, which further perpetuates existing racist systems.

“Voters get lost in the crossfire,” she said. “They have a hard time keeping track of who has power over what so they can hold the right people accountable. That confusion favors inaction which again preserves the status quo.”

“It’s going to be beyond powerful”

What Hudson is proposing, giving localities more autonomy with state backing and funding, is in some ways a scaled-up version of what the pandemic has brought for Charlottesville’s most determined communities — whether its access to jobs, mutual aid, food equity, affordable housing, anti-displacement strategies or philanthropic models based in solidarity not charity — people are prioritizing taking instruction from those on the ground, people who are going through the struggle themselves, and then supporting them, through resources or advocacy, to craft solutions.

Recently Hudson said she’s seen an increasing willingness in the government to focus on the economic inequality involved in criminalizing poverty, but not the racist part. She points to recently passed measures that decriminalize marijuana possession, or the increased threshold for grand larceny, or the waiving of home electronic ankle monitors fees.

But these measures are half-hearted, she said. If, instead of jail time, people possessing marijuana are fined, “it means it’s legal, but only for rich people for whom that penalty is not burdensome,” said Hudson. If a charge doesn’t have jail time attached to it, people aren’t required to be given a public defender, she said. “It lets us deal with the financial component of it, but not with the racist part, which is that Black kids are still getting stopped because they’re over-policed,” said Hudson.

Folley said the pandemic has opened the window for defining what a new “normal” can be. “Now we know that all this stuff we’ve been fighting for is possible, the only way we go back is if we get amnesia,” said Folley. “We can’t let this momentum die out. What happens after the marching?”

Hudson said the proof of a community moving towards anti-racist policies and practices will be in the budget. During the Great Migration, when more than 6 million African Americans moved north from southern states, recent research by Princeton University’s Ellora Derenoncourt shows that the only increase in spending on public services for the major destination cities was in police. To undo that legacy, Hudson said, Virginia needs to be intentional.

“We now understand collectively that when you have enormous historic debts to be paid you can’t make things fair without proactively righting racist wrongs,” said Hudson. “Taxes are an investment in each other, and in the society we all want to live in together.”

This week, in a government-wide move to reassess the Charlottesville City Schools’ partnership with the Charlottesville Police Department (CPD), officials announced a community-oriented process to reassess what safe schools look like, specifically without law enforcement. To back that process, and the resulting safe schools model, officials pledged the $300,000 in funding it was using to pay CPD.

Similarly, in the recently approved fiscal year 2021 budget, councilors voted to fund Home to Hope with $350,000, though this was $55,000 less than Walker wanted. And Hollie Lee, the city’s chief of workforce development strategies, who has helped build the Home to Hope program, said that the city is exploring moving some of housing-related funds into the program’s budget, to help participants find better homes.

Former Councilor Wes Bellamy, towards the end of his four years on City Council, reflected on the promise that Home to Hope and similarly structured programs will have on Charlottesville. “I think we don’t all quite get it right now,” said Bellamy. “We don’t understand the power. And I mean, we as a community. It’s going to be beyond powerful. It swings the pendulum in another direction and one towards true equity.”

Washington sees the vision. In the future, she pictures the group of peer navigators speaking across the country, at a convention perhaps, on a stage, behind podiums. People from all over will come hear how Home to Hope works, she said. “Because they want to incorporate this type of program into their re-entry, into their system,” she said.

And Merrick too, he sees it. “We want to make a movement,” he said. “We want people to see us when we’re not together.”

Together, they’ve built a home for hope.