Determined

This series uses the Social Determinants of Health as a foundational framework and guideposts to bring you stories of how the COVID-19 crisis has impacted some of our African American communities.On March 23, Gov. Ralph Northam stepped up to a press conference podium in Richmond. Flanked by two large signs reading, “Do your part, stay at home,” Northam declared thousands of businesses closed. “We are taking additional actions to keep Virginians safe,” he said.

At the time, there were 254 cases of COVID-19 in Virginia, and six people had died. Northam said the pandemic was going to hit Virginia hard in the coming weeks and social distancing was key. He’d already closed schools and just signed Executive Order 53, listing more than a dozen business categories as “essential” and allowed to stay open. They included grocery stores, pharmacies, medical and electronic retailers and both of Marcus Jones’s jobs.

The Shops at Stonefield in Albemarle County sits nearly empty during Gov. Ralph Northam's stay-at-home order, which could be modified around May 15.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

Jones, 48, works two jobs to support his family — one in the day and one at night. And while his night job, a restaurant, is technically able to stay open for takeout service, they did not. “We are temporarily closed due to the coronavirus,” says a prerecorded message to anybody who calls.

“My major money came from them,” said Jones, who’s worked there for 28 years. “That joint make you money, man. I’m in a different tax bracket when I work there.”

His daytime job, an auto shop, was also allowed to stay open. But instead of full-time, Jones is now working just three days a week there, not nearly enough to pay his more than $2,800 in monthly bills. Even more concerning for him is his multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune disease. His job requires him to be inside customers’ vehicles for extended periods.

“You’re getting in people’s cars, you don’t know where they’ve been, if they’ve been sneezing, if they’re dirty, tissues and stuff all over,” he said. “And I have to get right in there behind them and touch things. I have to be super protective of myself. And I’m not getting paid any extra dollars to go risk my life just so I can try to keep up with my bills.”

Financial well-being is a major factor in what’s known as Social Determinants of Health — the systems and collective societal behaviors that influence what happens to people in life. Studies show that for African Americans, these determinants are uniformly stacked against them, a result of generations of white-led systemic and individual acts of racism.

Quinton Harrell draws the analogy to an angiogram, where a doctor inserts a contrasting dye into a patient to reveal internal structures or bodily behaviors through an X-ray.

“This pandemic and crisis is that soluble dye in the anatomy of our community, and simply accentuating the fault lines that have always been there,” said Harrell, who chairs the Charlottesville Regional Chamber of Commerce’s Minority Business Alliance.

“Our main means of exchange is our labor”

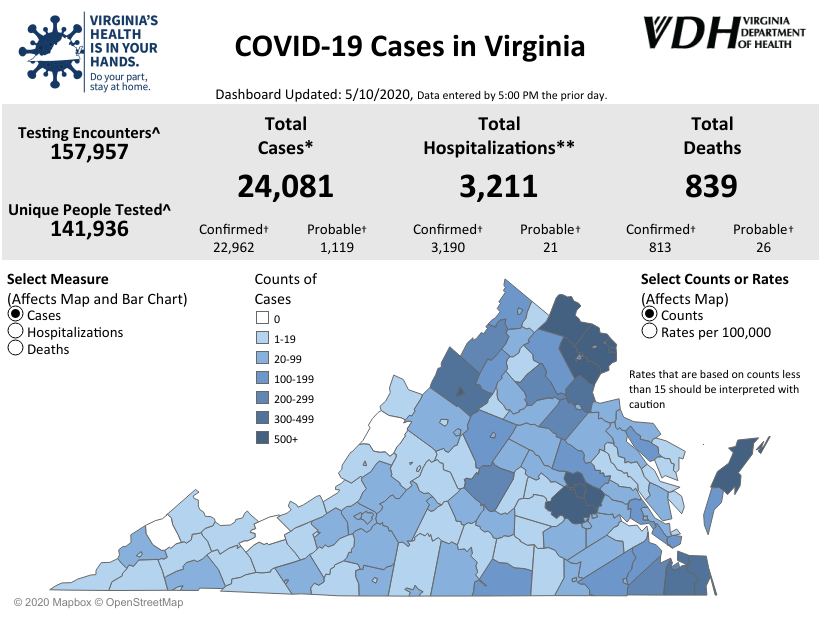

Virginia's COVID-19 statistics on May 10, 2020.

Credit: Virginia Department of Health

Throughout the state, more than 24,081 people have gotten COVID-19 as of this article’s publishing, and at least 839 people have died from it. As the pandemic has spread, and businesses have stayed open or closed their doors, it’s become clear that people with essential jobs are also the most at risk, because they have an increased likelihood of coming into contact with the virus. Some of those local essential jobs are doctors, nurses or hospital staff who make closer to, or even above, the Charlottesville area’s median household income of $58,933.

But many of those essential workers have jobs in grocery and retail stores, restaurants and gas stations — some of the largest employers here. Most of those workers barely get paid the $35,000 it takes for a family of three to survive here without any subsidies. At least 1 in 4 area residents don’t make this much, according to financial data. And with the COVID-19 pandemic, these jobs take on a new factor: a high physical proximity to others, coworkers and customers.

What’s more is that Jones is working three days a week at the car shop, so he can’t apply for unemployment insurance. Neither will he receive it if he quits. And so, he figures, while it doesn’t come close to earning a “living,” it’s better than nothing.

Customers keep their distance while waiting in line at the Bank of America in Barracks Road Shopping Center.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

In the wake of near historic national joblessness levels, where at least 23.1 million people are out of work, and perhaps as many as 43.2 million, are on unemployment so far. Here in the greater Charlottesville region, an estimated 15,435 people, or 12.3% of the working population, are unemployed.

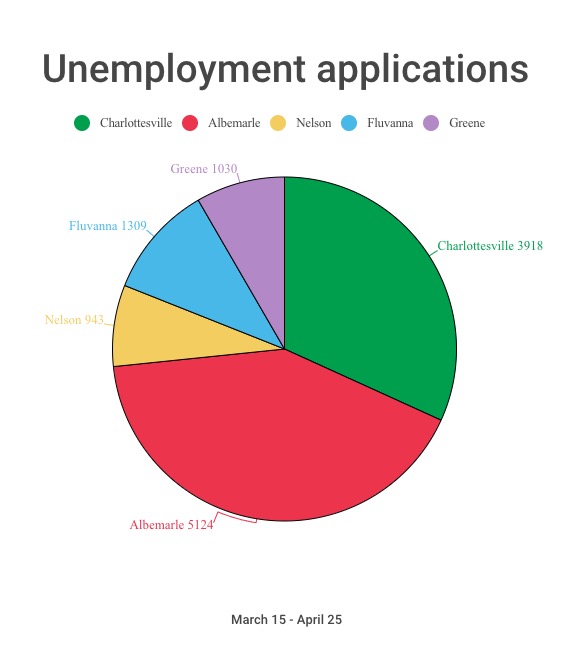

In just the six weeks following the statewide shutdown order, more than 12,324 people filed unemployment claims in our area — 3,918 in Charlottesville, 5,124 in Albemarle County, 943 in Nelson County, 1,309 Fluvanna County and 1,030 in Greene County. Last year, on average, there were about 3,111 people unemployed here, about 2.4% of the area’s 125,055-person workforce, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Credit: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

What is less trackable, however, is how many people like Jones are unable to file for unemployment yet have lost significant amounts of work and are severely underemployed in what work they do still have.

Since Liberation and Freedom Day in 1865, Charlottesville has had Black millionaires, and strong Black middle and professional classes have thrived here, just on smaller scales than in white communities. But this notion of underemployment — being employed at a job that pays an inadequate wage — has remained a constant through line for African American communities over the last 155 years. In fact, the labor market and job sectors here have never fully been racially desegregated.

In the 1920s, during the height of Jim Crow, also known as the Era of Racial Terror, the most common jobs for African Americans in Charlottesville were in the service and labor industries — laborers, servants, cooks and laundresses — according to the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center’s study of census records. For white people here, the most common jobs were as business owners and white collar sectors — as grocers, stenographers, bookkeepers or at the University of Virginia.

By 1940, on the heels of the progressive New Deal movement, the most common jobs for African Americans in Charlottesville were as maids, laborers, cooks and waiters, while white people worked most often in office jobs, as salesmen, carpenters and at UVA. Segregation did not simply occur by industry and type of work — it was even more glaring in the income each of these jobs paid.

Credit: U.S. Census Bureau

Black maids could expect to get paid $300-$500 a year, while Black laborers made about $300-$700 a year. Compare that to white office jobs, which paid between $900-$2,100, and white salesmen, who made between $1,170-$1,700. In 1940, the national median home value was $2,938, and monthly rent averaged between $20-$50, meaning that Black residents who worked in service and labor sectors were spending as much as 80% of their annual income on housing, while white workers in the white collar sectors spent about 30%.

The Charlottesville Downtown Mall during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and business shutdowns in Virginia, 28.3% of unemployment claims have been filed by African Americans, whereas 51.3% have come from white residents, according to the Virginia Employment Commission. This is racially disproportionate, as Black residents make up 19.9% of the state’s population, and white residents 69.5%. An inflated percentage of Black workers filing for unemployment suggests a greater degree of job loss or less generational savings or wealth to fall back on. Economists have posited this may also be directly linked to a workforce’s inability to telework, or work from home, strongly suggesting the types of jobs, and their corresponding value or pay, are still very much segregated by race.

“Our main means of exchange is our labor in a market and an economy where your ideas and money can money for you,” Harrell said.

“This stuff is really scary”

Nowhere has this pay inequity been more clear than at UVA, the area’s largest single employer, which — having forced enslaved Black people to build it and blocked African Americans from attending for another 125 years — today employs more than 28,000 people, about 16,000 faculty and staff and about 12,000 in the UVA Health System.

As an employer, UVA had some of the most light shed on it in 1996, with the issuance of the “Muddy Floor Report” by the university’s Office of Equal Opportunity Programs. It found nearly 7% of the greater Charlottesville region’s African American population worked at the university, and that they were paid the least and given the fewest opportunities to climb the ladder. African Americans made up 4.5% of the 2,327 employees in higher-wage professional non-faculty jobs at that time, whereas nearly 93% of those employees were white. Meanwhile, 53.2% of the lower-wage service and maintenance jobs were held by African Americans, and 43.2% by white employees.

The 1996 report detailed a culture of disrespect, discrimination and favoritism against African American employees throughout UVA. “There is a palpable feeling among the African American classified workforce that the university does not care about their plight,” it stated.

UVA’s hospital fared no better in the 1996 report, as 73.4% of African American employees earned less than $35,000, and none of the 128 total African American employees made more than $50,000 — whereas 135 of the 1,747 total white employees did.

For the last seven years, Marchell, who asked that her last name not be used, has worked at the hospital while for the past three years, her husband has worked at a UVA dining hall, feeding students and faculty. Since last November, they’d been experiencing housing instability and had been living at the Days Inn with their 4-year old child. They don’t own a car, so they needed to live close to work, but their jobs don’t pay them enough money to afford a place big enough on the open market. Since the pandemic, Marchell’s hours have been cut to 36 each week, and her husband, along with more than 800 other contract workers, was laid off. Every day, the 45-year old mother has to face potential COVID-19 exposure at work, and come home to her family. Her coworker just recently caught it and is now intubated.

“This stuff is really scary,” she said.

“They’re not understanding the opportunity cost”

Two weeks after the state-announced shutdown, and nearly five weeks since students left for spring break, UVA President Jim Ryan announced a $2 million fund for contract workers, also donating an additional $1 million to the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation’s Community Emergency Response Fund to support contract workers and low-income residents across the region affected by the pandemic. This came after several weeks of internal and external calls for UVA to pay the out-of-work contract workers, including a lengthy article in C-Ville Weekly by Sydney Halleman detailing the disrespectful way African American employees felt they were treated, as well as a massive pressure campaign waged by faculty, state officials, students and community activists. Marchell’s husband was able to get some of this funding.

The Campaign for a Living Wage — a student, faculty, community and worker-led coalition — launched in 1998, and has been pushing for more equitable incomes ever since, a rich history detailed in an essay published last year by professor Claudrena Harold, chair of UVA’s Department of History. Last year, Ryan announced that UVA would be raising its employee’s minimum wage to $15 an hour and moved later in the year to include full-time contract workers. But $15 an hour, after taxes, sends workers home with about $967 every two weeks, amounting to $25,142 a year. This is far less than the minimum $35,000 it takes to survive here subsidy free — that would actually require a minimum “living” wage of $21.50 an hour.

Marchell and Jones, whose first job has reduced hours and second shuttered, are some of the more than 3,500 households who have gotten assistance from the Community Emergency Response Fund set up by the CACF. The CERF operated in tandem with the COVID-19 Emergency Resource Helpline, a partnership between the city of Charlottesville, Albemarle County, the United Way of Greater Charlottesville and Cville Community Cares — an activist network rooted in organizing resistance to the 2017 white terrorist attacks — to give an average of $750 to area households experiencing hardship. All told, the CERF paid for whole months’ worth of rents for Southwood and public housing residents, given $680,000 to 22 non-profit organizations doing frontline work, and $3.1 million in direct payments, more than 65% of which went to African Americans, said Eboni Bugg, director of programs for CACF.

This is a perfect example of the opportunity cost that results from not fostering an equitable system, said Harrell, the chair of the Charlottesville Regional Chamber of Commerce’s Minority Business Alliance. He used a business analogy to look at historical and systemic racism.

“A common mistake of business owners is concentrating on the income of the revenue statement, and ignoring the balance of the assets and liabilities,” said Harrell. “In Charlottesville, the affluent, white business and power structures have historically benefited from the revenues of the system that has predominantly tilted towards them. Comfortably, they’ve not fully understood the opportunity costs of systematically relegating a significant economic contributor — African Americans — to the sidelines of prosperity.

“There’s been tremendous opportunity costs over the hundreds of years in our history because of a certain business interest that believes they’re due all the spoils, at all costs.”

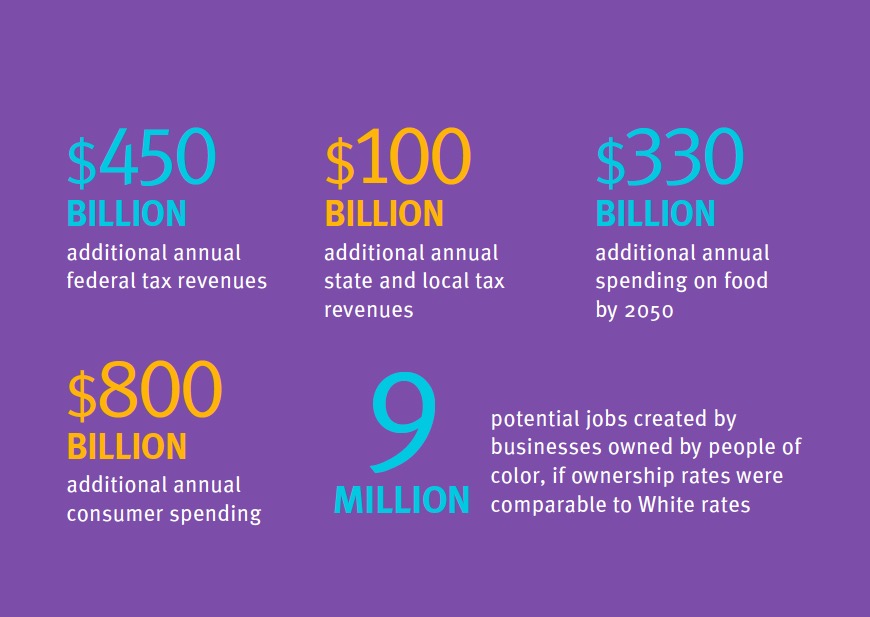

A 2018 report conducted by the non-profit research firm Altarum for the W.K. Kellogg Foundation found that by reconfiguring U.S. housing, education, healthcare, criminal justice and employment systems to be racially equitable, the nation would produce an $8 trillion gain in gross domestic product.

Credit: W.K. Kellogg Foundation

“Raising the average earnings of people of color to match those of whites by closing gaps in health, education and opportunity would generate an additional $1 trillion in earnings,” the report stated. “Where will these additional earnings come from? They will come from the economic growth that a more productive workforce brings to meet growing global demand, and the growth that families of color themselves support with greater spending power and more financial security.”

“And then, boom”

For as many people as the CERF has helped, there are those like Tina who didn’t apply because she felt others were in more need. For three decades, Tina’s worked for a local-area government and, between her and her husband, who’s a maintenance technician, they’ve always been able to make ends meet. But last September, her husband was injured on the job, and after a surgery and a recovery period, finally got a new job in March. For six months, they had been surviving on just one income, and it had been tough, but they’d done it.

A man sands wood on Third Street Northeast near the Charlottesville Downtown Mall.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

“And so then you’re thinking, ‘Finally, a breath of fresh air, he’s going back to work,’” said Tina, who asked us not to use her real name. “And then, boom.”

The COVID-19 pandemic hit. And because he was one of the most recent hires, her husband, not even two weeks back at work, was laid off. And it’s not just them — they take care of Tina’s elderly parents, on top of the regular bills, car payments and rent — the struggle and determination is all around them.

“I have church family that have been impacted by it,” she said. “They lost their job or got laid off. They went into work and basically were told that was their last day. I have a few neighbors that have been impacted, too, they don’t have work.”

Many African Americans, like Marchell’s husband, work in the food world, one of the largest industries in Charlottesville. To date, the state has processed more than 80,000 unemployment claims from this industry alone — 23% of all claims. But according to the Virginia Employment Commission, it provides the lowest wage of any industry in Charlottesville, at $421 per week. The average overall weekly wage for all industries here is $1,028. What’s more, according to Antwon Brinson, owner of Culinary Concepts AB and creator of the city’s GO Cook program, the highest paid sous chef positions earn on average $18-$24 an hour. Everyone else on the line — pantry, hotline, junior sous chefs — get paid roughly $11-$18 an hour, he said. Lowest on the scale are dishwashers, typically getting paid $10.50-$12 an hour.

In the first week of the shutdown, several Charlottesville GoFundMe efforts were immediately set up, some streamlining the sale of gift cards and certificates, while encouraging people to order takeout and delivery, and some that even connected restaurants directly with frontline workers, helping two key causes at once. Collectively, they raised more than $130,000 and facilitated many thousands more in communitywide purchasing. They included long lists of area restaurants, but noticeably absent were popular Black-owned restaurants: Mel’s Cafe, Royalty Eats, Pearl Island, Angelic’s Kitchen and many others. All of these crowdsourced initiatives were started by white residents. When this lapse of inclusion was brought to their attention, they added the food establishments to their lists. But this delay or afterthought when it comes to support for African Americans is one that has permeated much of white Charlottesville’s pre-COVID economic actions, as well.

Sober Pierre, owner and operator of Pearl Island Foods, and Executive Chef Javier Figueroa-Ray.

Credit: Lorenzo Dickerson

In the period between 1904-1916, there were a dozen Black-owned barbershops, 11 Black-owned grocery stores, and scores of other Black-owned businesses . Today, according to research and data collected by local business owners and entrepreneurs Destinee Wright and Cordell Fortune, there are more than 150 Black-owned businesses in our area.

In the immediate days following the COVID-19 crisis, the city’s Office of Economic Development launched its Building Resilience Among Charlottesville Entrepreneurs grant program with about $85,000. It awarded up to $2,000 to small businesses experiencing hardship. But of the 149 businesses to apply, only 19, or 12.7%, were African American-owned. Minority groups overall, however, were well represented, and the BRACE program ended up giving 69 grants out. About 40% went to African American-, Latino-, Asian- and white women-owned businesses.

Hollie Lee, the city’s chief of workforce development strategies was stumped about the low Black participation. Lee has led the creation of the city’s successful GO job training and placement programs, helped to launch both the Business Equity Fund and the Home to Hope program and has provided staff support for the Minority Business Commission. She’s one of the most tapped-in city staff members when it comes to connecting with African American businesses.

“I really wish more Black-owned businesses had applied — I feel like I know so many of them,” said Lee, who emailed, called and contacted a lengthy roster of Black-owned businesses. “I do think that sometimes, with us being a government, people think there’s a lot of red tape attached to it. And that’s one thing that I have really worked hard on over the years, to try and eliminate so much of that, because I know that could be the thing that makes someone say, ‘forget it’ and move along, like it’s more headache than it’s even worth. But if people would just go through the process, they’d know it’s really not that bad.”

Lee said they even revamped the grant application process to try and get rid of some of that red tape. They put it all online and made it mobile friendly so people could use their phones to apply. They also eliminated the formal interview process and the requirement for vendor registration with the city of Charlottesville. These efforts have come forward in no small part because of the city’s past — between 2012-2017, the city awarded less than 2% of contracts to minority-owned businesses. Last year, former Councilor Wes Bellamy led the creation of the Business Equity Fund for minority and women-owned businesses. And so, to ensure more opportunity for minority-owned businesses to get access to capital, Lee launched a 1%-3% interest loan program as part of the BEF, awarding $55,000 to 11 businesses — eight Black-owned, one Asian-owned and two women-owned.

In the coming weeks, Lee said she’s readying another round of loans to help with business recovery efforts. Further, every fall, the city hosts a minority and women-owned business expo, which they’re in the process of adapting to a virtual online platform to unveil in the coming months to get those businesses more exposure and publicity.

For Harrell’s part, he’s using this time to evaluate, self-educate, and reflect on where he’s come and where he still wants to go. The system can work better if you have more of the right people contributing to the system, and key to that is collaboration, prioritizing Black-run initiatives and exchanging ideas, goods and supports, he said.

“We can take this opportunity to better understand the game, which has been ruled by a certain few people,” he said. “We could accomplish things that have never been seen or done before that will be historically magnificent.”

Back to Determined.

Next story: Determined to Be Nourished