A deafening boom woke Larry Green from a sound sleep just before 4 a.m. the morning of Oct. 9, 2020.

The Charlottesville man shot out of bed and rushed to his front window. Directly in front of his house he saw the mangled remains of a car smashed against a tree. The impact had ripped the vehicle in two, he remembers. Half lay crumpled in the median, while the other half was nearly a quarter mile down the road.

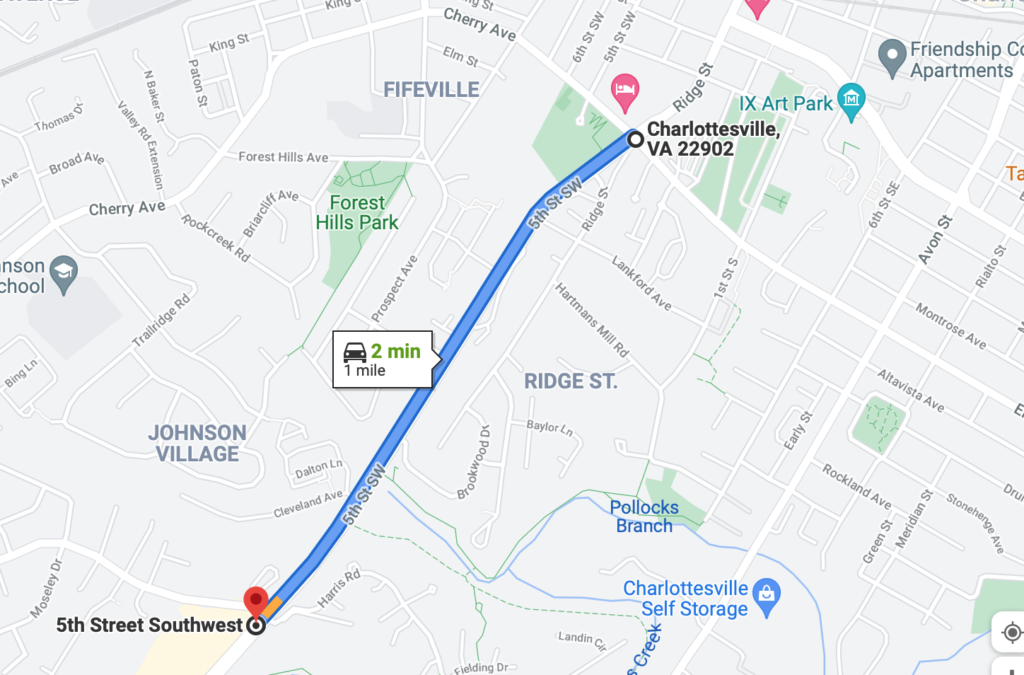

It was a shocking scene, Green said. But it’s one he sometimes sees several times a year. There have been four fatal crashes in less than two years along this mile-long stretch of Fifth Street Southwest, between the Wegmans shopping center and Tonsler Park.

“I’m usually the first one there,” Green said. He stood in his driveway last week looking across the road toward a makeshift memorial at the tree in the median. Two young men died in that October wreck.

Friends and relatives put up a memorial to the two men who died in a car crash on Fifth Street Southwest near Tonsler Park on Oct. 9, 2021. The memorial remains in Feb. 2022.

Credit: Jessie Higgins/Charlottesville Tomorrow

The most recent fatal crash was in early January, less than two blocks from the scene of the October 2020 one. After that wreck, a local group called Livable Cville put renewed pressure on the City Council to do something to make the road safer. (Community members first came forward with concerns about the road in October 2020 after four people were killed on the road in just three months.)

The city responded last week with a plan to reduce the street’s speed limit from 45 miles per hour to 40. The Council is expected to approve the speed limit reduction at its next regular meeting on Feb. 22.

It’s an important step, officials say, but lowering the speed limit alone will have a limited effect on the road’s overall safety.

“The design encourages high speeds,” Brennen Duncan, the city’s traffic engineer, told Charlottesville Tomorrow in October 2020. “That stretch of road [between Harris Road and Elliott and Cherry avenues] is straight and wide, and there is nothing giving people the signal to slow down.”

Residents who live there refer to it as a “race track.” There are no stoplights on the mile-long stretch of road between Harris Street and Cherry Avenue. And drivers do reach high speeds along that section of road, especially during non-peak hours when traffic is light.

“You can get going really fast,” said Allen Sanders, who lives in an apartment complex between Prospect Avenue and Fifth Street. “That is a race track.”

This one mile stretch of Fifth Street Southwest between Harris Road and Cherry Avenue is wide, straight and has no stoplights signals to slow traffic.

Credit: Screenshot of Google Maps taken on Feb. 14, 2022

The city could redesign the road to slow traffic, Duncan said. They could install another stoplight, build a roundabout, or even reduce the number of lanes from four to two and physically narrow the street.

Such actions, though, would have other consequences.

Fifth Street is a main artery to and from town — it connects downtown Charlottesville with I-64. Hundreds of cars travel in and out of Charlottesville along that road every day.

Any effort made to slow traffic could create intense congestion, especially during peak hours, Duncan said. More congestion would also increase the number of minor accidents.

“The road is already so congested, especially around the Wegman’s intersection,” said Rebecca Meadows, who lives near Tonsler Park. “I totally avoid it from about 4 p.m. on. If they slow down traffic too much, it’s going to be even more congested.”

The city plans to hire an engineering firm this winter to look at the different options for Fifth Street to “not only come up with options, but really look at cost-benefit,” Duncan said.

“We want to bring all the options before Council and the public and have a real discussion about it,” he added. “Anything that comes with improvements in one area is going to have a negative effect in another area. So we just want to make sure that everyone is aware and on board with what those negative effects might be.”

The study is expected to take between 3 and 6 months.