As Buford Middle School students hustled between their third and fourth period classes last week, rain fell fast from the sky over Charlottesville. The weather picked up just before the bell rang, and the students who hurried outside for their class change found their sneakers caked in mud and their sweatshirts and backpacks damp: The covered sidewalks connecting the various school buildings are leaking.

Students and teachers inside weren’t faring much better. The school roof leaks in multiple places, and it’s often just as dreary inside the school — some classrooms have no windows at all.

Less than a mile away, at Westhaven, residents of Charlottesville’s oldest public housing community propped their inefficient windows open to deal with the humidity while preparing lunch on outdated stovetops. All the while they prayed that their ceilings wouldn’t start leaking again. In front of one apartment, an orange and black plastic yard sign swayed back and forth in the weather, announcing a young Westhaven resident’s graduation from Charlottesville High School.

At Westhaven, Charlottesville’s oldest public housing community, a family continues to celebrate a 2021 Charlottesville High School graduate nearly a year after the fact.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

Both Westhaven and Buford were built in the mid-1960s and are in desperate need not just of repairs and renovations, but reconstruction and redevelopment. For decades, community members have asked city officials to fund these two reconstruction projects, among others.

City councilors have acknowledged repeatedly that these housing and school improvement projects are a priority for the broader community’s wellbeing, and have said that they want to support them financially.

These conversations aren’t just theoretical. The city hired a local architecture firm last year to draw up plans to rebuild Buford. And in late January, Westhaven residents met for a workshop to plan for the upcoming redevelopment of their homes. “Redevelopment is coming! Let your voices be heard,” the event flier read.

But a decision made by the Virginia General Assembly in February tossed those plans into the air: City Council hoped that it would get permission from the commonwealth to levy a local sales tax to pay for Buford’s reconstruction. All three bills that would have allowed the city to do so, were killed.

Without that money, the city’s options are limited.

Now, officials are faced with having to fund the school and the public housing projects using the city’s existing Capital Improvement Program fund — and there’s not enough money in that fund to afford both.

The school project alone would bankrupt the Capital Improvement Program fund for four or five years. City Council is debating raising local real estate taxes to grow the fund, but even if they do there won’t be enough to pay for everything, City Councilor Michael Payne told Charlottesville Tomorrow.

“It’s a very crunched budget,” Payne said. “Everything we have to do has to involve looking at the trade-offs of any decisions and looking at the numbers as they are. It’s not great news. And so it’s uncomfortable, because I think there are tradeoffs that are unfortunate to have to look at.”

It’s a dilemma that’s left community members exasperated.

“I know the budget is tight, and they’re trying to put money everywhere,” said Shymora Cooper, a former public housing resident and mother of a current Buford student. But when it comes to housing and education, “I shouldn’t have to pick. I shouldn’t have to pick,” she said, shaking her head.

The problems at Buford

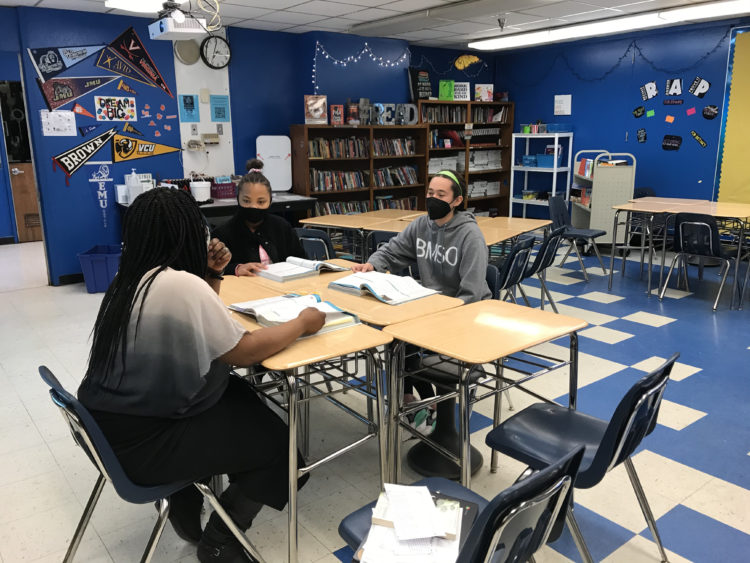

Some folks “see dollar signs” when it comes to the school project, whereas “teachers see student faces,” said Buford teacher Cianna Washburg (left). “We see that change needs to happen, because the students deserve better. I don’t know how much it costs for a new building. All I know is that the students that I come across deserve a school that meets their needs. And that’s it.”

Credit: Erin O'Hare / Charlottesville Tomorrow

Cianna Washburg teaches middle school language arts because she believes deeply in the power and the joy of storytelling.

“We all have a story to tell,” Washburg said one rainy Thursday morning, sitting at the front of her blue-walled Buford classroom that she decorated with holiday lights, a yellow paper butterfly, and an assortment of posters.

Her gaze drifted toward a nearby shelf holding copies of the novel Refugee. Washburg’s students read the book in the fall. When they started, many didn’t know what a refugee was. They read articles and watched videos to learn, but the most powerful examples came from their peers who themselves are refugees, Washburg said. More than one student got up to say, “my family, too.”

The school building is where these conversations, connections and moments of growth happen.

But Buford isn’t an easy place to have impassioned conversations.

Washburg shares a classroom wall — and a soft wall at that — with another seventh grade teacher. Once upon a time, that wall was meant to allow teachers to open up the space and collaborate across classrooms, but now it means Washburg’s students can hear what’s going on next door. If Washburg is giving a test while her neighbor is leading a collaborative assignment, her students get distracted by conversations, by a movie showing, or a song playing. Once, a student piped up and said, “Hey, they’re rolling dice!”

“The walls are not set up for learning,” Washburg said, adding that she frequently asks her students to quiet down. “It really shuts off this opportunity for collaboration. And I think that’s what learning is about.”

Some of Buford’s science labs were updated in 2013, but the school is now more than 100 students over capacity, and the updated labs can’t accommodate all of the students. This science classroom has one sink, making labs difficult and sometimes impossible.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

Buford’s 700 or so students have to adapt not just to noise from hallways and other classrooms, but from the aging HVAC system. To an auditorium that’s not large enough to hold a school-wide assembly. To a school with a leaky roof — and the mold issues it causes. To getting soggy when they change classes on a rainy day. To a science classroom that has only one sink and thus can’t be used for labs.

Not being able to do a science lab could be detrimental to students like Buford eighth-grader Nadia Taylor-Kinney, who wants to be a surgeon or a research scientist.

She wishes the school’s bathrooms were nicer, too, that all of the sinks and soap dispensers worked and that the pad and tampon machine in the girls’ rooms were filled more frequently.

She wishes the school was more accessible, and that her grandmother, who sometimes has trouble getting around, could come watch her play volleyball in the gym. Right now there is only one handicapped-accessible entrance, and it’s a metal wheelchair lift located in a small, dark, brick-and-concrete room to the side of the gymnasium building.

This elevator lift, located in a narrow hallway next to the Buford gymnasium, is the only way anyone who uses a wheelchair or another mobility aid can access the gym. Accessibility is yet another issue with the school, which was built in 1966, long before the Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

“Look at how the foundation is,” Nadia said, sitting on a beanbag chair in one of the school social worker’s windowless offices, voices of other students and administrators audible through the closed door. “I think the school needs more positive vibes. The school needs a whole upgrade,” she said.

The list of needs goes on.

Students have school-issued computers for their lessons, but most classrooms have just a couple of power outlets, Washburg said, pointing to the two in her own classroom. That makes it difficult to set her students up for success. Dead computer, no lesson.

Students have also adapted to crowded classrooms — Buford is more than 100 students over capacity. And some of those classrooms don’t have windows.

“This is a luxury. This is a luxury!” Washburg said, pointing to the two narrow windows letting slivers of natural light into her classroom. (A few minutes later, she showed Charlottesville Tomorrow the reading specialist and special education teachers’ shared classroom, which has no windows at all. Same goes for the library.)

“When kids spend eight hours a day here, they often spend more time with their teachers than their families,” said Buford Assistant Principal John Kronstain after pointing to the place where water seeps through the gymnasium wall and gathers on the floor. “And this is the home we give them?”

That brownish-grayish-greenish stuff where the floor meets the wall shows where the rain seeps into the gymnasium.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

The $75 million fix

After more than a decade of talks about the conditions at Buford, in 2021, the city hired Charlottesville-based VMDO Architects to look into the problems with the school buildings and draft plans to fix them. (VMDO is a sponsor for Charlottesville Tomorrow.)

In the fall, the firm recommended a $75 million project. The plan was to completely redesign the campus by adding new buildings and renovating existing ones. The rebuild would add capacity to the school so the district could move sixth graders from Walker Upper Elementary School into Buford and then move all of the city’s pre-K kids to Walker.

It’s a hefty price tag, said Wyck Knox, a partner with VMDO and lead on this project. But, the longer the city waits to start it, the more expensive it is going to be.

Read more about the school reconfiguration project in this story from fall 2021.

When the project was first discussed about a decade ago, a version of the Buford project cost about $32 million. It was turned down because officials said the city didn’t have the money, Knox said.

“And we delayed it. And we keep doing that for various reasons, and that’s how we’ve gotten in trouble,” Knox said. “Construction inflation in 2021 was 13.5%. And normally, the average is like 3.5% to 4% a year.”

Knox estimates that the price of the project rose by about $800,000 per month in 2021 due to rising construction costs.

Time, “that’s what’s killing us,” Knox said. “Our need is not going to go away. If we build more housing and do more things in the city, we’re going to bring more people, [which means] more students.”

Buford hallways are dark. Lockers aren’t needed in most schools at this point — students are not carrying around backpacks full of books, since most texts are digital — and the cost of removing them is prohibitive, said Buford Assistant Principal John Kronstain.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

There are other options. City Council could decide this year to fund a less expensive — less extensive — renovation.

The least expensive option would involve renovating — but not adding natural light or additional capacity to — two of Buford’s four buildings. That’s about $33 million.

The other six options come in between about $52 and $75 million. And that’s if the project can be taken to bid as soon as possible, Knox said.

Finding the money

Whatever option the city chooses, the money will come from its Capital Improvement Program fund. That account is funded primarily by local real estate tax and generally brings in about $15 million a year. (That’s a fraction of the city’s entire annual budget of about $217 million, but it is the fund the city uses to pay for repairs or construction of city-owned buildings and infrastructure.)

“Typically, our Capital Improvement Program fund is $70 to $80 million for five years, and that’s a whole bunch of little projects added up together. When you talk about one project at $75 million, that’s pretty impactful,” said Krisy Hammill, the city’s senior budget and management analyst.

In order to not totally bankrupt the fund — which would pay for, say, bridge repairs in an emergency — Council and staff “either have to cut out other things or bring in more money,” Hammill said.

In recent budget work sessions, Councilors have discussed doing both.

Cutting both the downtown parking garage project and the West Main streetscape project would add $18.5 million to the Capital Improvement Program fund. Charlottesville City Schools has offered to contribute about $7 million that it received from federal stimulus money to reopen schools and recover learning loss in the wake of COVID-19.

Raising taxes would increase the city’s revenues, too. Increasing the local meal tax by 0.5%, to 6.5%, would garner an additional $1.25 million for the fund. Increasing real estate taxes from the current 95 cents per $100 of value to $1.05 per $100 of value would add another $9.2 million — this particular increase could be done over a few years, or all at once.

Altogether, that might cover the least expensive version of the Buford project.

The city could also sell bonds to fund the project, but that would increase its debt, and that money would eventually come due, tightening future budgets.

Councilors are also looking for state and federal grants.

But even if the Council takes all these options, paying for a new school will still leave multiple projects unfunded, Payne said in a March 10 budget workshop. He came ready with a list:

- cost of living wage increases for city staff;

- the fire department positions funded with one-time grants;

- money for Charlottesville Area Transit to achieve 15- or even 30-minute routes;

- Piedmont Housing Alliance’s proposed Park Street housing project;

- building and repairing sidewalks;

- Climate Action Plan implementation;

- and future public housing redevelopments, including, Payne confirmed in an email to Charlottesville Tomorrow, redevelopment of Westhaven.

Council will discuss the Capital Improvement Program fund during a budget work session on Thursday. Any formal decisions will likely be made during a City Council special meeting on April 12.

Between now and then, the Council will have to decide what size school project it wants to do — if any — and how to fund it, said Hammill.

During a recent Council meeting, interim City Manager Michael Rogers suggested a conservative (2 cents per $100 of value) real estate tax increase over the course of a few years, instead of raising the tax significantly all at once. Such a small increase could delay both the Buford and Westhaven projects further.

It’s a familiar refrain, Shymora Cooper, an organizer with Charlottesville United for Public Education, told Charlottesville Tomorrow.

Public housing

Advocates and longtime friends Shymora Cooper (left) and Joy Johnson (right) stand outside the Westhaven Nursing Clinic on Hardy Drive. Cooper is an advocate with Charlottesville United for Public Education, and Johnson with the Public Housing Association of Residents. Both say that education and stable housing together are crucial to a child’s success.

Credit: Eze Amos / Charlottesville Tomorrow

City officials “keep kicking the can down the road” when it comes to funding both housing and schools, Cooper said while sitting at a table in the former Westhaven nursing clinic building, which now serves as the office for the nonprofit advocacy group Public Housing Association of Residents.

“If we are truly going to invest in our kids, we need to invest across the board: schools, resources, wraparound services,” housing, and more, she said. Instead, she said it feels like the city keeps saying, “we’re gonna give you a little bit, and we’re going to continue to give you crumbs.”

Cooper knows the tune — the one made by the can being kicked down the road — by heart. She grew up in Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority’s Michie Drive community and attended public schools. When her mother died, she moved to the South First Street public housing community and raised her children there until recently, when she purchased her own home.

For decades, residents of Charlottesville’s seven public housing communities have asked for better living conditions, she said. There was a sewage leak, among other issues in Crescent Halls, the building for seniors and folks with disabilities. Residents in other CRHA communities had to wait months for leaky roofs to be repaired, or for broken appliances and heating systems to be fixed or replaced. These are just a few of their concerns.

Read more: “After years of advocating for redevelopment, Crescent halls residents break ground on renovations”

Read more: “South First Street groundbreaking marks phase one of resident-led redevelopment”

Their voices were eventually heard. Over the past couple of years, the city started redeveloping some of its public housing communities. Crescent Halls, South First Street, and Sixth Street are all in various phases of renovation and construction, work that has been guided by what residents say they want and need.

Joy Johnson, a public housing advocate and founder of the Public Housing Association of Residents, is thrilled that redevelopment is finally happening there, but she is upset that other public housing communities, including her own, will have to wait.

Johnson has lived in Westhaven since 1983, raised her children there, and now helps raise her grandchildren there. Johnson is an elder in her own community and has been recognized on the national stage for her advocacy. She has been asking for better living conditions in Westhaven and other CRHA public housing communities since before founding PHAR in 1998.

The Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority’s South First Street public housing community is in the midst of redevelopment, something residents have asked for for decades.

Credit: Erin O'Hare / Charlottesville Tomorrow

The redevelopment work that is already physically underway will continue. But “in our current draft budget, there is not funding for those future phases” of redevelopment in communities where redevelopment has not yet begun, including Westhaven and Michie Drive, said Councilor Payne.

“If our budget were adopted as is, everything not currently in the budget — of which those future phases are just one example — couldn’t be funded for potentially 8 to 10 years under staff’s current projections.”

Another decade, again.

But residents — particularly the children — need it now, advocates say.

“If they have stable housing, chances are somebody’s going to excel,” said Johnson. “If you don’t have a stable home, and you’re living in the Salvation Army, or you’re living with family members — because that can be problematic — then that child doesn’t really have a place where he can properly do his homework and learn.”

Schools and housing ‘go hand-in-hand’

Adults aren’t the only people thinking this through. Nadia, the Buford student, knows that the stable home her grandmother provides will help her achieve her goals.

Home is “a place of comfort,” she said. “When you’re tired, you always have your room and your bed.”

Nadia’s face lights up when she thinks about the breakfasts her grandmother cooks, and the thought of her favorite dinner follows quickly: Fried chicken, greens, candied yams. Homemade rolls. “Delicious,” Nadia said, closing her eyes and lifting her smiling face toward the ceiling.

“My grandma makes it a safe space for me,” she said. “She makes sure that I have everything I need.”School and home are the two main places in a kid’s life, she said, and both should be places that kids want to be. It’s why she thinks the City Council should “split the money fifty-fifty, use half the money for schools, and half the money for affordable properties.”

“Everybody needs a safe space to go to,” she said.

Like Nadia, former public housing resident (and new homeowner) Cooper knows how education and housing work in tandem to provide a bright future for young people.

Cooper has excelled, Johnson said. Her three children — students at Old Dominion University, Charlottesville High School, and Buford — are also poised to excel. She wants that for all the children growing up in low income communities.

“A community that invests in housing as well as public education, it’ll build a strong community,” Cooper said. “You can’t invest in housing without also investing in schools, because where do you think these kids are going to school? The same kids that need housing are the same kids that are going to the schools that need the money as well.”

It’s true: As of fall 2021, 46% — nearly half — of the students enrolled in Charlottesville City Schools are considered economically disadvantaged, said T. Denise Johnson, supervisor of equity and inclusion for the district.

The redevelopment work that is already physically underway at some of CRHA’s properties, like South First Street, will continue. But “in our current draft budget, there is not funding for those future phases” of redevelopment in communities where redevelopment has not yet begun, including Westhaven (shown here) and Michie Drive, said Charlottesville City Councilor Michael Payne.

Credit: Mike Kropf / Charlottesville Tomorrow

The Virginia Department of Education considers students “economically disadvantaged” if they are eligible for free and reduced meals, eligible for Medicaid, receive Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, are a migrant or are experiencing homelessness.

The percentage of economically disadvantaged students is greater at Buford: 52.8%, according to VDOE.

Read more about how Buford Middle School and Walker Upper Elementary became more socioeconomically disadvantaged.

“Housing is important. Education is important. They go hand in hand,” Cooper said. “I don’t know how you’re going to do it, but figure out how you fund both and not continue to, again, kick that can down the road and put a little bit here and a little bit there and not fix the whole problem.”

Johnson shook her head in unison with Cooper, her earrings making a twinkling sound.

“Everyone deserves housing, and everyone deserves to learn,” said Johnson. “It’s a human right.”