As the fate of Charlottesville’s Confederate statues remains uncertain, the future of the places that surround them have remained largely on hold.

When writer and historian Ibram X. Kendi visited Charlottesville on Tuesday, Charlottesville Tomorrow sat down with him and Jefferson School African American Heritage Center Executive Director Andrea Douglas to talk about the city’s monuments.

“I think that it’s always important to state basic truths about the Confederate States of America,” Kendi said.

“The majority of Southerners during the Confederacy were actually opposed to the Confederacy that’s imagined today as a sort of source or lineage of Southern pride.”

Kendi wrote the New York Times bestseller, “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America” and founded the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University.

Monument Myths

Kendi said that half of the South was enslaved when it seceded from the United States and that the majority of white people did not own slaves. The vast majority of those nonslaveholding whites opposed the Confederacy, Kendi said, and nonslaveholding white women rioted against the lack of food during the Civil War.

Kendi said that those who deny that the Confederacy was racist are denying what the founders of the Confederacy said. The title of Kendi’s book comes from a speech by Jefferson Davis, who became the president of the Confederacy. Davis said that African American inferiority to whites was “stamped from the beginning” and “the will of God.”

“In Charlottesville, that rhetoric was rampant in the placement of those statues. … There [was] a very deep discussion about white supremacy and how whites are being placed in a place almost of enslavement themselves [after the Civil War],” Douglas said.

Douglas leads tours of Charlottesville’s Confederate monuments with University of Virginia professor Jalane Schmidt. The tour now is available online, thanks to community radio station WTJU.

The tour describes how the United Daughters of the Confederacy supported the installation of the statues while they approved new history books, including one that glorified the Ku Klux Klan.

The tour also recounts content from the installation speeches, like the description of emancipated African Americans as a “tyrannous majority,” even though Black Charlottesville had just dipped under 50% of the population.

Antiracist Space

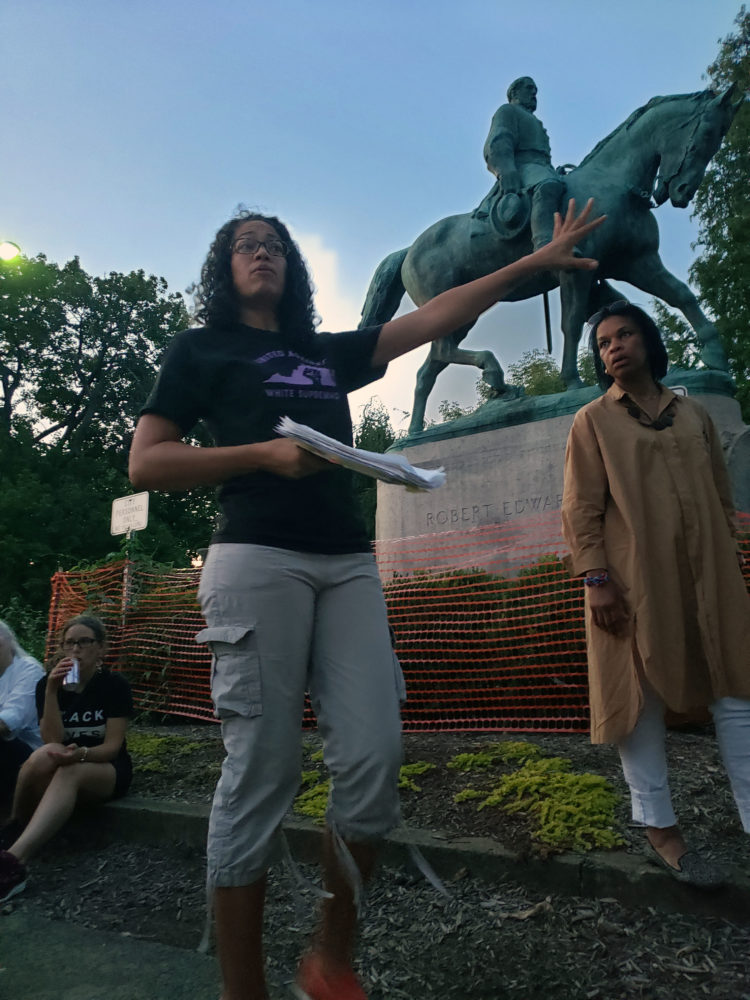

University of Virginia professor Jalane Schmidt and Jefferson School African American Heritage Center Executive Director Andrea Douglas lead an Aug. 9, 2019, walking tour with historical contextualization of various monuments throughout Court Square and at Market Street Park in downtown Charlottesville.

Credit: Charlotte Rene Woods / Charlottesville Tomorrow

Kendi was in Charlottesville to talk about his new book, “How to Be an Antiracist.”

Charlottesville Tomorrow asked Kendi and Douglas whether the term antiracist could be applied to a space and, if so, how they would make the Court Square area antiracist.

Both Kendi and Douglas agreed that the monuments to Confederate Gens. Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson need to be out of public spaces where community events are held and that the place to learn about slaveholders and segregationists is in museums.

“They belong somewhere, but I’m not sure they belong in those places where they are,” Douglas said of the statues in Market Street and Court Square parks.

“From my standpoint, we should be honoring people who challenged slavery. We should be honoring people who pushed for human equality and freedom,” Kendi said.

Douglas said that she was moved to start the tours after realizing how little most people knew about the statues. Providing context is less about being antiracist, she said, and more about telling the truth about what power can do.

“I think clarity is most important here,” she said.

Just signage, she said, was a passive way of dealing with the ideologies the statues represent and that the objects are objects of their time.

Slow Change in Court Square

Charlottesville, Albemarle community leaders gather around unveiled historical marker for lynching victim John Henry James.

Credit: Norah Mulinda/Charlottesville Tomorrow

Charlottesville has a blueprint for how to remake its public spaces.

Following advocacy from then ninth-grader Zyahna Bryant and Councilor Wes Bellamy, the city convened a Blue Ribbon Commission on Race, Memorials and Public Spaces. In December 2016, the commission issued a report recommending that the city either move or transform the Lee and Jackson statues.

Charlottesville first voted in early 2017 to relocate the Lee statue from its downtown area. Since then, the city has faced a series of legal setbacks that it could appeal to higher courts or that Virginia lawmakers could eliminate after November’s elections.

Along with a list of other people and places that could be commemorated throughout the city, the Blue Ribbon Commission recommended that the city replace the plaque at the “Number Nothing” building in Court Square that memorializes where enslaved people were sold.

In addition, the group recommended that the city commission a new memorial to those who were enslaved and place it in or near Court Square.

Some of the Blue Ribbon Commission recommendations are well underway.

The city now celebrates Freedom and Liberation Day on March 3 to recognize the day in 1865 when slavery ended in the area. Albemarle County and the University of Virginia also celebrate the holiday.

The city decided to rename the Lee and Jackson parks to Market Street Park and Court Square Park, respectively.

Douglas and Schmidt led efforts to memorialize local ice cream salesman John Henry James, who was lynched in 1898. The city and county collaborated this summer to erect a new marker to James in Court Square.

Soil from the site of the lynching of John Henry James sits in a vessel in the Albemarle County Office Building. The county on Wednesday, July 17 unveiled a traveling exhibit commemorating and contextualizing the 1898 lynching.

Credit: Mike Kropf/Charlottesville Tomorrow

However, other commission recommendations are moving slowly, and the plan of whether or when to get them done is unclear. One of these is augmenting the slave auction block at Number Nothing.

“No one has ever come to me and said, ‘How is work going on replacing the plaque in the sidewalk?’” said city preservation planner Jeff Werner. “If council had been expecting something to be done, it didn’t get to me.”

Councilor Heather Hill said that the City Council has said several times that they want to see something more prominent in the place of the slave auction block.

Hill serves on the city’s Historic Resources Committee. She said that she has been trying to clarify next steps on both the slave auction block and the broader parks redesign.

In July, the City Council told staff that it would like to see options for how to better memorialize the auction block return within a few months.

Werner said that it is unclear where Blue Ribbon Commission recommendations fit into his work plan. Most of his time is devoted to the Board of Architectural Review, and he spends nearly all the rest of his time on other development-related questions like demolition permits and historic district surveys.

In monthly meetings, the Historic Resources Committee has been creating aluminum plaques that tell a fuller story of the Court Square area, posters about Vinegar Hill for the construction barricades around the Center of Developing Entrepreneurs on West Main Street and markers for a future Vinegar Hill Park at that site.

“Yes, all these are wonderful ideas, but they all take resources and they take time. We’re trying to get done what we can,” Werner said. “I think we’re doing a pretty good job.”

Charlottesville Mayor Nikuyah Walker interviewed Kendi about “How to Be an Antiracist” on Tuesday evening. Listeners packed the auditorium at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center.